VIEW PDF

Private museums are revitalising the art scene in India, but the state-run ones need to wake up and smell the coffee—Saloni Doshi

A few years ago, a group of art lovers in Mumbai came up with a plan. They wanted to make the magnifi-cent, but largely unvisited, National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) a popular destination. After all, Mumbai had fought so hard to get its very own NGMA, and it was a shame that it had failed to live up to its promise. Unlike the footfall-attracting, ever-busy Prince of Wales Museum across the street, the NGMA drew a much thinner crowd. Art lovers and painters dropped by, but students, tourists and the average person continued to stay away; many Mumbaikars didn't even seem to know or care about the excellent exhibitions inside the rotund sandstone pile. Something had to be done to animate it

"The Nanavati Charitable Trust that runs the Nanavati hospital in Mumbai offered to give the NGMA a gift store and a cafeteria," says noted architect Pinakin Patel, who was part of the informal NGMA Bachao group during Sarayu Doshi's reign. The world over, gift shops are "sticky spaces" in museums, where visitors gather and loiter. Patel offered to design and run the store. "I made the plans, got them approved by the heritage committee, but after a frustrating period for all concerned, the government refused to allow any such activity."

All across the country, state-run art institutions are faced with similar chal-lenges. Bureaucracy and art, with a few honourable exceptions (the revitalised Prince of Wales being one of them) make for incompatible bedfellows. Little wonder then that the postlib decades have witnessed the rise of a number of private cultural initiatives whose objective it is to enliven and modernise the art scene. Private collectors from Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and Coimbatore have stepped up to the plate, setting up their own institutions and museums - modest versions of the Guggenheim or MOMA—and creating salons for liter-ary, political and artistic debate.

Others in the private sector have given generous purses and signed fruitful private-public partnerships. A trophy case is the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation, which granted Rs 5 crore towards the restoration of the civic-run Bhau Daji Lad Museum in Mumbai. The once mouldy building was so tastefully restored by INTACH that it won the UNESCO 2005 Award of Excellence for Conservation.

In another public-private marriage, the Prince of Wales Museum has dedicated a whole gallery to exhibiting the Jehangir Nicholson Collection on a long term basis. The collection can travel internationally and within India and be uploaded on the web. Jehangir Nicholson, a cotton merchant and former sheriff of Mumbai, collected relentlessly and generously through the 86 years of life, and his mammoth collection has long awaited an appropriate exhibition space.

One of the earliest instances of a mutually beneficial arrangement was in Bangalore, in 1982, when businessman H Kejriwal, with the monetary support of the state government, built the Chitraka Parishad. Spread over 20,000 sq ft, housed his collection of 375 paintings and 255 sculptures of folk art, contemporary European art and Indian modern and contemporary art. Kejriwal had cleverly adopted the American model of opening a private museum to share a private collection with the public, a concept not prevalent in India at the time.

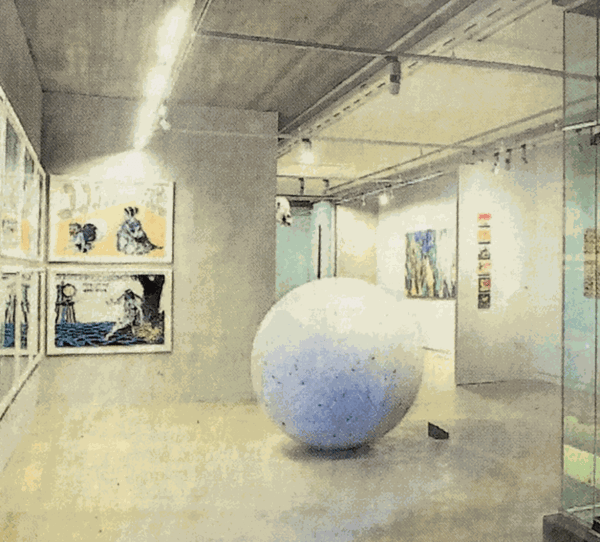

Art Foundation started by Lekha and Anupam Poddar in Gurgaon, Haryana.

The Poddars, who collect some truly radical art, wanted Devi to be a space to foster a meaningful dialogue between various art practitioners in the subcontinent in order to enhance our understanding of a shared history. Devi recently hosted Resemble Reassemble, an exhibition of Pakistan's top contemporary artists, curated by celebrated artist Rashid Rana.

Setting up the show wasn't easy. "Ship-ping of artworks from Pakistan to India and money transfers were a problem," says Poddar, who says it is challenging to run a non-profit organisation like this without any government support. But his response to the show made the effort worth it. Not far from Devi is the KNMA or the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art established by Shiv and Kiran Nadar of CL Technologies, Like Devi, the 13,000 i-ft KNMA is a site for the confluence of ideas and creative thought rather than a nere exhibition gallery.

In Mumbai, Neville Tuli, founder of the auction house Osian's, has for long been passionate about starting a muse-1m, Oslanama. It will be housed in the erstwhile Minerva Theatre, which he has bought and is remodelling. Over the years, Tuli has been steadily buying up world-class objet d' art and cinema memorabilia — from samurai armour to Buddhist thangkas to Marlon Brando's letters — to showcase in the museum, which, plagued by infrastructural and monetary problems, shows no imminent signs of opening.

A boat ride from Mumbai in verdant Alibaug, Pinakin Patel has successfully opened the Dashrath Patel Museum for the living artist whose 60-year-old col lection boasts ceramics, paintings and photographs that chronicle the evolution of the republic of India from Independence to the present. Patel, a senior Progressive Group artist who was the first director of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, has collaborated with luminaries like Charles Eames, Louis Kahn, Henri Cartier-Bres-son and Frei Otto. The museum is curated by his close friend, the eminent art critic Sadanand Menon.

In the eastern hub of Kolkata, Rakhi Sarcar (of CIMA Art Gallery) is a managing trustee of the KMOMA (Kolkata Museum of Modern Art). This triangular private-public partnership between the state government, the Centre and private sector envisages a state-of-the-art museum scheduled to open in 2013. It will exhibit Indian and international art and have an academic wing to promote cultural studies. The museum has been designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the architects of the Tate Modern, London and the Beijing Olympic Stadium. It is equipped to show digital, new media and installation art, which, sadly enough, most state-run museums are not equipped to do (art is still seen as something in a frame on a wall). Today, in the digital age of the internet, interactive games and computers, most museums are in need of a drastic upgradation.

Going south, veteran collector and sugar baroness, Rajashree Pathy has taken her consuming passion for art to the next level by creating a world-class museum and educational institute called COCCA (Coimbatore College of Contemporary Art) in the sleepy town of Coimbatore to generate art awareness through outreach programmes. She has dedicated 15,000 sq ft of her old textile mill to this intellectual project, which opens next year.

Meanwhile, private galleries are curating and hosting large retrospectives, something that the museums should rightfully be doing. "I have seen a few museum quality shows (in Mumbai) within the limited space of a private gallery—the Bhupen Khakhar retrospective and Chemould's 40th anniversary are the few that come to mind," comments art critic Girish Shahane. Recently, Saffronart in Mumbai published a well-curated catalogue for the retrospective of Krishen Khanna and is following it up with one of K M Adimoolam. The Dhoomimal Art Gallery in Delhi recently organised a large F N Souza retrospective curated by Yashodhara Dalmia at the Lalit Kala Akademi. The retro had a number of adjunct events like film screenings, poetry reading, talks and curated walks. "There are many great artists in India who deserve this respect," says Khorshed Pun-dole of the Pundole Art Gallery in Mum-bai. "But the galleries do not have the space, money or the bandwidth to collect the most important works of the artists from all around the world; this is plainly the role of a museum."

Financial difficulties apart, the other more contentious charge is that of elitism. Galleries may be organising excellent retrospectives but they cannot invite a large public audience, which a museum can best do. Ultimately, we need good, vibrant and democratic museums. As architect Romi Khosla puts it, "There is a vested interest for the nation state in preserving these museums as specimen racks of our golden past. The degree of control that a government exercises on them is a direct function of its desire to exert its authority, the more it wants to counter new ideas about culture and portray its own version." Kekoo Gandhy, who lobbied hard to get an NGMA in Mumbai points out, "Even though professional bureaucrats are doing a good job at the central level, the need to decentralise this power is important for the growth of art and culture at the state level, or else the museum will soon become fossilised and private players will fill in the void."

Poddar agrees. "At the policy-making level, there is a need for clarity on how

'culture' is defined. For example, photography, video and new media should be included as art," he says. "Or else, the state-owned museums will be missing out on an important turn in cultural practices. At the bureaucratic level, young and fresh curatorial talent has to be pumped in, before these institutions die out slowly. They are on the verge of being museumised."